Monday, January 7, 2008

Radar technology to jump from microwave ovens to home heating systems?

Posted by John Keller

It all began with a melted candy bar.

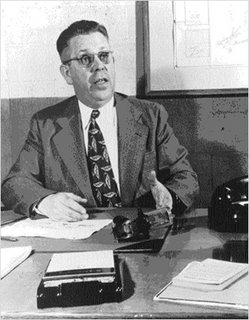

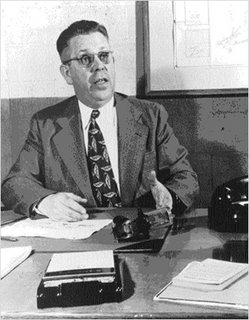

Noted Raytheon Co. engineer Dr. Percy Spencer in 1945 was doing some research into the new technology of radio direction and ranging -- better known as radar -- at a company lab in Waltham, Mass. As he tested a new vacuum tube called a magnetron, he noticed that a candy bar he had in his pocket had melted.

Following a hunch, he applied energy from the magnetron to popcorn, and later to an egg (the popcorn popped, the egg exploded). He realized that this new device heated food from the inside, and the microwave oven was born (remember the Radarange?).

Radar technology was the genesis of a household appliance so common that today it outsells gas ranges. We don't use them to melt candy bars anymore, but who could be without one to defrost a pound hamburger and heat up that tepid cup of coffee?

Today microwave technology is being used to develop so-called "non-lethal" weapons popularly known as the "pain ray," which can heat a person's skin to uncomfortable levels, but cause no lasting harm. This kind of weapon likely to be used for crowd control, driving off intruders, and similar applications.

Dr. Spencer's discovery of how to harness microwaves for heating isn't stopping there, however. Now scientists are considering ways to use that same radar technology to comfortably warm people in their homes during cold weather, reports David Hambling in Wired's Danger Room blog.

Says Hambling in his story headlined Pain Beam: Central Heating Of The Future:

Such a system is far from practical use, however. As Hambling's story points out, people are generally very cautions about microwave energy, and might be hesitant to turn their homes into giant low-power microwave ovens. I can just hear a kid up in his bedroom shouting, "I'm cold; turn up the nuker!" Watch out. If mom or dad turns it up too high it just might melt the candy bar in his pocket.

I live in New Hampshire where the winters can get really cold. I'm not sure if this approach could prevent pipes from freezing, and I don't know about the effect of cold on those widescreen LCD flat-panel TVs and small appliances like iPods.

Yet stranger things have happened, and adventurous scientists should continue looking into this approach. At one time we never thought that radar would power our ovens, any more than we believe now that our microwave ovens could ever heat our homes.

Posted by John Keller

It all began with a melted candy bar.

Noted Raytheon Co. engineer Dr. Percy Spencer in 1945 was doing some research into the new technology of radio direction and ranging -- better known as radar -- at a company lab in Waltham, Mass. As he tested a new vacuum tube called a magnetron, he noticed that a candy bar he had in his pocket had melted.

Following a hunch, he applied energy from the magnetron to popcorn, and later to an egg (the popcorn popped, the egg exploded). He realized that this new device heated food from the inside, and the microwave oven was born (remember the Radarange?).

Radar technology was the genesis of a household appliance so common that today it outsells gas ranges. We don't use them to melt candy bars anymore, but who could be without one to defrost a pound hamburger and heat up that tepid cup of coffee?

Today microwave technology is being used to develop so-called "non-lethal" weapons popularly known as the "pain ray," which can heat a person's skin to uncomfortable levels, but cause no lasting harm. This kind of weapon likely to be used for crowd control, driving off intruders, and similar applications.

Dr. Spencer's discovery of how to harness microwaves for heating isn't stopping there, however. Now scientists are considering ways to use that same radar technology to comfortably warm people in their homes during cold weather, reports David Hambling in Wired's Danger Room blog.

Says Hambling in his story headlined Pain Beam: Central Heating Of The Future:

The temperature may be below zero, but you're not about to adjust the thermostat. Even in a light shirt, you're warm and comfortable – even if your breath does form an icy plume. Why? 'Cause you've got the energy-efficient heating system of the future: millimeter waves from your domestic Active Denial system -- or, as we've come to call it, the pain ray ... microwave heating systems could cut household heating bills by 75 per cent. And since microwaves cause light bulbs to fluoresce, such a heating system could also double as the power supply for a system of wireless lights.

Such a system is far from practical use, however. As Hambling's story points out, people are generally very cautions about microwave energy, and might be hesitant to turn their homes into giant low-power microwave ovens. I can just hear a kid up in his bedroom shouting, "I'm cold; turn up the nuker!" Watch out. If mom or dad turns it up too high it just might melt the candy bar in his pocket.

I live in New Hampshire where the winters can get really cold. I'm not sure if this approach could prevent pipes from freezing, and I don't know about the effect of cold on those widescreen LCD flat-panel TVs and small appliances like iPods.

Yet stranger things have happened, and adventurous scientists should continue looking into this approach. At one time we never thought that radar would power our ovens, any more than we believe now that our microwave ovens could ever heat our homes.

Comments:

<< Home

If the sole source of heating was microwave, then all inanimate objects in the home would be near outside temperatures, depending on ratio of heat emitting bodies to square footage of the home. If it's 0 degrees F outside, then inside air and objects might be 10-20 degrees F? Like tile floors, cutlery, dishes, telephones, vinyl or leather upholstery furniture, toilet seats?

Post a Comment

Subscribe to Post Comments [Atom]

<< Home